an unwelcome childhood

...with Dr. Galit Atlas's book, Emotional Inheritance: A Therapist, Her Patients, and the Legacy of Trauma.

I have two waning-moon-shaped scars on my body. Burn scars.

One sprawls across the area between my chin and the beginning of my neck, the other expands on the inside of my right arm, just above the crease of my elbow.

I’m told that when I was little and had just started walking, my father contracted Tuberculosis from getting severely cold when he was out drinking night after night. He got admitted into hospital.

One Sunday afternoon after we all got back from visiting him, I wandered into the kitchen on my own and burnt myself in a pot of boiling oil that was set in a bin on the floor, just outside the kitchen.

“Can you believe it? Then we had to go back to the hospital again that afternoon, the nurses were not happy with us!”

I’ve always known this story. I have always hated the scars.

To the point of pretending they weren’t there, and the story didn’t exist.

I’m not sure how we arrived here but, one day my mother is talking haphazardly and she tells me this story from when I was born:

In the labour ward, after a relatively difficult delivery, my gran walks in, this is our first meeting, and she says, “You silly baby, you almost killed my daughter!”

Well, hello to you too grandma.

“One day, you asked me to make you some scrambled egg,” my sister says to me in a random text message.

“I said no” she says,

“Then I walked back into the kitchen and there you were, standing on a chair in front of the stove, making your own scrambled eggs.”

We laugh. It makes me feel great to know I’ve always been an independent woman; since I was little.

I’m nine years younger than my sister, my only sibling.

When we go to family gatherings (almost always on mom’s side), no one knows me. They remember me, but they don’t actually know my face or who I am. They know about me but they don’t know me.

They don’t refer back to old stories when they see me like they do with my sister. They have no memories with me; I never spent time with them.

It’s my sister who’s in all the anecdotes with everyone who ever lived in the area, including deceased neighbours. She knows the family that lived in that house before the family that lives there now. For every house.

She’s the one who remembers our grandfather and all his wives; their children, and their houses. She remembers who was mean, and who was kind. Who got to go to gambling in casinos with grandpa and who boiled water for his hot-water bottle every night.

She knows the people who died, and how they died. She knows everybody by name.

And they know her.

Me? I’m mostly hanging around her, smiling awkwardly.

“Oh, this is Siphumelele, your mother’s last one?”

They ask my sister, not me. She answers them. No one talks to me because it’s awkward. They know I’m “S’thembile’s little daughter,” “Cebo’s little sister.” But they don’t know me

It seems like all the best stories are from years before I was born. By the time I came around, it seems things were settled. My parents were already married and living together (unlike when they had my sister and my grandfather hadn’t given them the plot to build a house yet and my mother left my sister with her family…hence all the stories).

My grandmother was back from Johannesburg too, and living with my parents and my sister. Her sons, my uncles, had already been released from prison; one by death, one by escape, and the third by serving out his time I guess. Or maybe sickness.

There were no more crime stories from Johannesburg. No more taxi-washing at our house and old cousins bringing mischief.

When I was born, life had “settled,” and revealed its real face, shocking everyone into normalcy.

Piecing together snippets from here and there, I know in the years leading to my arrival my dad was drinking the heaviest he’d ever drank in his time with my mom. He was coming home later, and his blue Mini Cooper had already been crashed on a drinking escapade with friends.

My mother was already working as a nurse; the only person I’ve ever known her as, even though she was so much before that I’m told.

When I arrived, “the good ol’ days” were truly the good old days; gone and binding the people who had lived them together in a tapestry of memories. A circle of stories that would glow when they got together and shared the memories, finishing each other’s sentences.

To this day, this circle lives. It comes alive when we get together with my mother’s family (and some of my dad’s family too) and my sister is an intrinsic part of those circles on both sides of our parents’ families.

I am in neither of these circles. I have no stories, no memories.

Partly because I was born so much later after my sister, and mostly because life started to change drastically around the time I was born and more so as I grew up.

When I came onto the scene, everybody had memorised the script and become familiar with their section of the set, the plot was rolling.

I came in colicky, desperate for attention, sensing that I was late and no one was interested in catching me up. Unlike a character who comes in a little later in the story, my part was not written originally. The story was moving along just fine and I came in like a piece of furniture that suddenly comes alive and needs lines.

There were no words for me.

I was uninvited, and a surprise.

I would be given everything I need; the egg, the pan, the stove, and the high chair. But no one was going to scramble anything for me. They were busy being whatever they were before I came. I would have to put the ingredients together for myself, and find a way to exist in the margins.

When my mother divorces my dad, I am 10.

We move to a new town, a new neighbourhood. All the kids here already know each other, they have memories together from when they were little. They tell me about them sometimes. They let me hang around this thing of theirs that’s been going on long before me.

“I’m uninvited here.”

It’s true again.

And it becomes more and more true in other instances:

The high school I go to, which accepts me despite my not having gone to its feeder schools. As a result, I lose my few friends from junior school. I have to start a new journey with people who are deep in theirs.

My mother takes a nursing job far away and can only come home on weekends. We have no one in our family that can come stay with me at this point so she has to hire people to come and live with me.

There’s a new one every couple of months. I constantly come home to an empty house, the latest one gone having left without notice. I am guilty because apparently no one can stomach living with me.

No one wants me in their story.

I long for continuity but I am not wanted I quickly learn.

My story is one where the character traverses a new world with each page turn.

“I don’t belong, anywhere.”

Not even like the greasers in S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, which becomes my favourite book in freshman year because of the title. At least they have each other.

Soda has Johnny.

I have no one.

So I try to make sure I need no one.

In Emotional Inheritance: A Therapist, Her Patients, and the Legacy of Trauma, 2022, Dr. Galit Atlas talks about babies sometimes coming into the world uninvited, for all manner of unfortunate reasons.

She then talks about the adult who was an unwanted baby. The pre-discursive neglect and longing for attention that we grown up with, a kind of attachment that if unregarded, will be reenacted in all our future attachments.

Those who expect to be loved often make sure others love them, while those who expect to be neglected might evoke neglect (Atlas 2022).

“Unregarded” is the key word.

And yet, for some of us it’s easy to disregard our original attachment style; especially when it’s being unwanted. For some of us, no one will tell us that when we showed up, we were unfortunately, an inconvenience.

How could anyone admit to such a thing; to not wanting a baby around, even in the deepest recesses of their minds?

They might obliquely tell you that your dad was descending into addiction and your mother was carrying everyone on her back. But they won’t say, “And so, when you came, they already had their hands full.”

Maybe they didn’t even see it that way, and yet that’s the way it was.

I blame no one.

Instead I relish the freedom of being able to understand.

My mind remembers, so my body is free to forget (Atlas 2022).

For the first time, I allow hot tears to boil for my waning-moon burn scars. For the toddler I was, whom no one was looking out for because they were riddled with their own stresses.

For the first time, I can read the pattern and come up without any shame. Pain still, but no self-blame.

Pain that I was the last one to arrive everywhere I went, and too far behind to catch up. Pain for how I started to unconsciously repeat this pattern of neglect and feeling left out:

The self-sabotage that has endured.

I have been the last one to arrive at every job I’ve gotten, and the attention and approval I have felt entitled to so early on would’ve eventually come had I stayed longer. But I left, resolved that I’d never get it; used to being unwanted.

Like how I left parties and gatherings early in university and then hurt for my lack of solid relationships.

I left because in those first few minutes of standing there on my own it felt like no one would ever come my way. And I couldn’t go to anyone, because I felt I was the only visitor and they all belonged. And didn’t want me there.

I’ve quit new things and people very quickly because the message comes back louder and clearer each time:

“I’m not wanted here, my presence is a nuisance.”

This, accompanied by a slew of physiological symptoms that help enable my flight. My nervous system responding with sirens because it is pressed in an all-too familiar way:

“I am an inconvenience here, I should go. I must take care of myself alone.”

It is often easy to recognise those people who were not fully invited into this world. They seem like visitors, outsiders who might leave at any minute (Atlas 2022).

Oh, and haven’t I been the essential outsider…

Oh sweetheart.

When I look at it like this finally, I want to embrace myself, like I do on my yoga mat with my back pressed to the floor and my knees curled up tightly to my chest. I want to say to myself,

“I want you here.”

Before, when I looked at my inability to foster relationships I thought I really didn’t belong.

When a friend of a friend died tragically last year, I was devastated.

It felt so unjust.

Someone like me should’ve died, not her. She had solid, beautiful friendships; her mother adored her, not clung to her, and the rest of her family worshipped her. She was an integral part of the story she was in.

It felt like in my story, my part was so transient, so marginal. I could just cease to exist and it would all carry on seamlessly. No one was around me most of the time, no one needed me. I longed for rest from aching for attention.

In a seminal 1929 paper titled “The Unwelcome Child and His Death-Instinct,” the Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi described people who came into the world as what he called “unwelcome guests of the family.” Ferenczi made the direct link between being an unwelcome baby and having an unconscious wish to die (Atlas 2022).

With most negative information, the natural assumption is that we are better off not knowing. That in fact, what we know, especially of origins and family, should be positive and good for the sake of our confidence in the world.

This is not true.

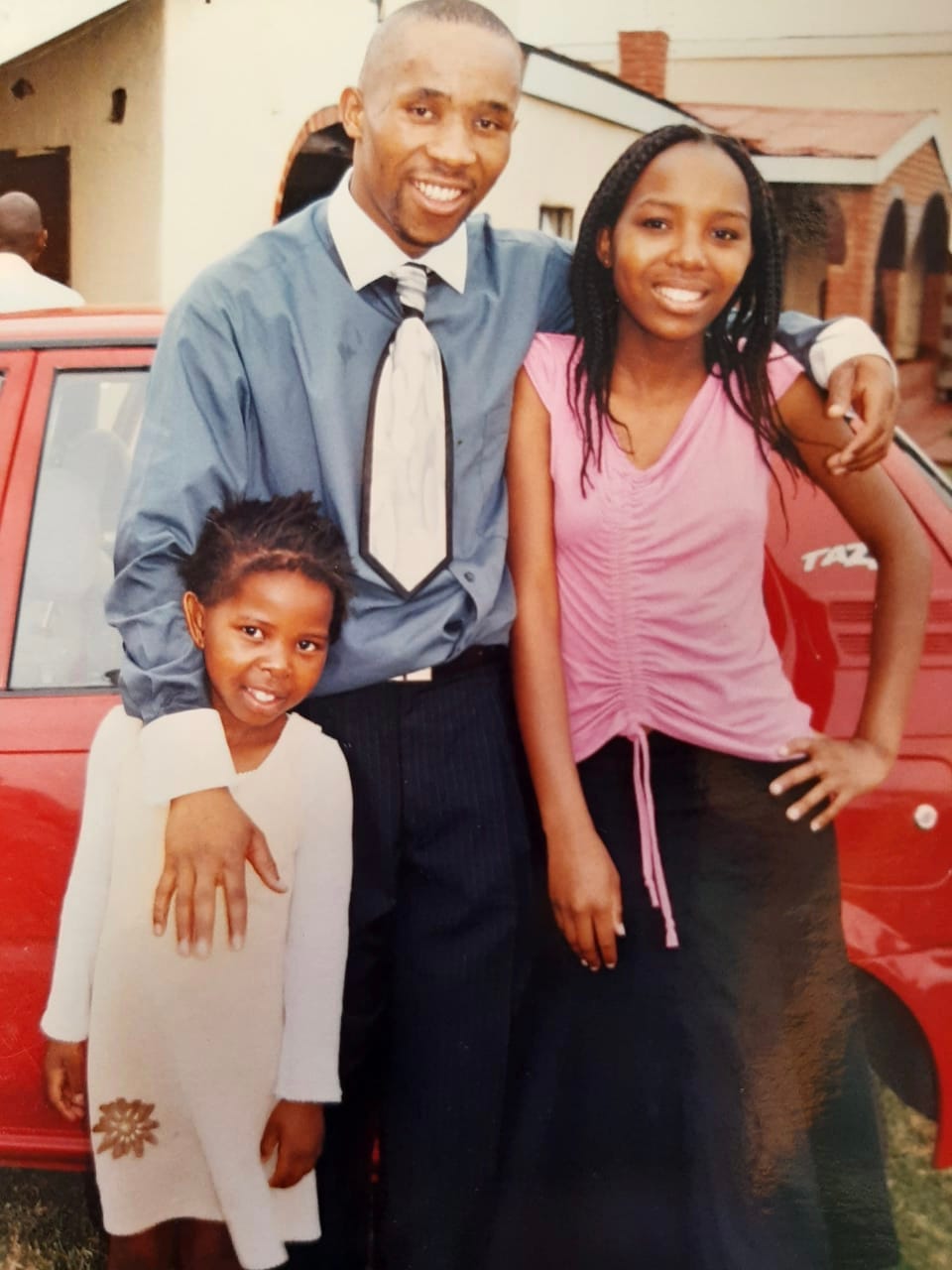

The few photographs I have from my childhood would have me believe I was front and centre in absolutely everything my family did after I was born. And even if this were true, I still wouldn’t be an emotionally and psychologically mature person.

It’s not about having had the perfect attunement in our childhood relations. It is actually about having relations that can be repaired time and time again. Dr. Galit Atlas eloquently explains it in Emotional Inheritance 2022:

…a good relationship is the result not of a perfect level of attunement but rather of successful repairs (Atlas 2022).

It hasn’t helped me build better relationships to chide my ego and try to”conversion-therapy” myself out of “codependency.” A buzzword I’ve picked up as I’ve blindly searched for the reasons why joining people scares me and I run away even though I want nothing more than to stay.

It’s actually that my body holds memories of having to hang back, and ask very little of the people around me because they were dealing with a lot.

My body holds memories of crying and understanding that no one is coming.

My body holds memories of standing on the outside and looking in.

My body holds memories of fending for myself.

My body [knows] what my mind couldn’t remember (Atlas 2022).

But now, now my mind remembers; so sweet, sweet body, you are free to forget now sweetheart.

Dear reader, friend, please, try to get a hold of a copy of this book, Emotional Inheritance: A Therapist, Her Patients, and the Legacy of Trauma, 2022, by Dr. Galit Atlas.

You will, be moved.

Be well.

Yours,

Siphumelele.